For centuries, wars were fought over land, oil, or ideology. But in the 21st century, a quieter, slower, yet potentially more devastating conflict is emerging — the battle over water. As climate change accelerates droughts and depletes natural reserves, and as global consumption rises, water is transforming from a basic human right into a strategic commodity.

In rural Chile, entire communities are watching their rivers run dry while avocado plantations owned by multinationals flourish under intensive irrigation. In India, major tech hubs struggle with water shortages so severe that companies have begun trucking in water daily. In the United States, cities like Las Vegas invest billions in drawing water from ever more distant sources. Meanwhile, global corporations such as Nestlé and Coca-Cola secure long-term water extraction rights — often paying only symbolic fees while bottling the liquid and selling it back at a premium.

This isn’t science fiction — it’s today’s reality.

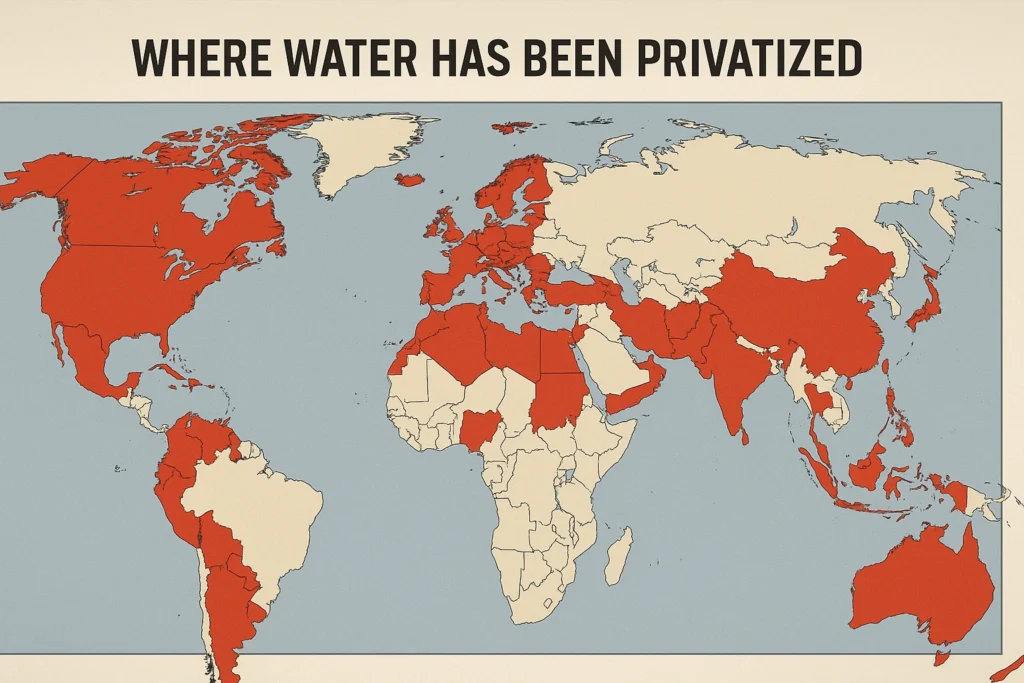

According to the United Nations, more than 2 billion people already lack access to safe drinking water. By 2030, global demand could outstrip supply by 40%. While some governments treat this as a wake-up call, others quietly privatize water infrastructure under pressure from debt, international lenders, or corporate lobbying.

So who really owns water?

Legally, water has long been considered a common good. But in practice, laws vary wildly. In some U.S. states, water rights are tied to land ownership or historical use. In parts of Africa and Latin America, ancestral water access is now challenged by extractive industries. In Europe, public resistance to water privatization is growing — after failed experiments led to higher costs, lower quality, and social unrest.

A striking example: In 2000, protests erupted in Cochabamba, Bolivia, when a private company backed by the World Bank gained control of the city’s water supply — and tripled prices overnight. The people fought back. The uprising, known today as the Water War, forced the government to cancel the deal. Yet similar tensions simmer elsewhere, often unreported.

Meanwhile, the market sees opportunity.

Water futures are now traded on Wall Street, just like oil or grain. Investors frame it as a way to manage risk — but critics warn: When water becomes an asset, its value is no longer measured in life, but in price per share.

Yet there is resistance.

Citizens’ movements, indigenous groups, and local cooperatives are reclaiming control. Cities like Paris and Berlin have re-municipalized their water systems with notable success — lowering prices, improving quality, and increasing transparency. Tech innovations like atmospheric water generators or AI-managed smart grids offer hope, but without equitable policy, they risk becoming luxuries for the few.

The question is no longer whether a water crisis is coming.

It is already here — just unevenly distributed. The real question is: will water remain a shared resource of life, or will it be captured, traded, and controlled like any other asset?

One thing is clear:

In the age of climate emergency, access to clean water is no longer just a humanitarian issue. It’s a political, economic, and moral battle — one that will define our century.